In late 1983, Nick Cave arrived back in Australia, four years after he and his fellow members of The Birthday Party had left Australian shores to pursue the band’s career in Europe. With The Birthday Party having imploded under the weight of Cave and guitarist Rowland S. Howard’s competing creative desires – and copious drug use – Cave sought to exploit the mythology that had evolved around hisenfant terriblegothic punk persona.

Interviewing Cave for Stiletto magazine, writer Clinton Walker, who’d rubbed shoulders with his subject in the halcyon days of Melbourne’s Crystal Ballroom venue in the late 1970s, probed Cave on his next creative move and his relationship to the world around him.

“I’m sort of doubting the value of the creative process,” mused Cave at the time. “I’ve always sort of qualified my life in terms of, ‘At least I’ve got these records, I’ve done this, I’ve done that…’ It’s a load of bullshit. I don’t want to be too precious about it but I find myself leading exactly the same lifestyle as all the people around me, who I thought were totally directionless and lost individuals, and excusing myself from that because I made records.”

30 years later, and it’s hard to reconcile the latent self-doubt in Cave’s past observations with the accomplished musician, poet and performer – and prodigious worker – who forms the subject of Iain Forsyth and Jane Pollard’s drama-documentary feature, 20,000 Days On Earth.

Forsyth and Pollard had originally worked with Cave when he’d approached them to produce some film clips for Cave’s 2008 album with The Bad Seeds, Dig!!! Lazarus Dig!!! The film is a narrative conceit of a day in Cave’s life, from the moment of waking to the drawing of the curtain after a typically explosive Bad Seeds live show. Rather than explore Cave’s role in creating or challenging his own mythology, Forsyth says, “We wanted to portray Nick as someone who tells stories, constantly churning everything through the mill of the imagination.”

“We like the idea that our rock stars should be beyond our grasp, that they should be reaching for something greater,” adds Pollard. “We also wanted to speak to bigger ideas, to probe universal themes like creativity and mortality.”

Cave was interested in the concept of the film, and a willing editorial contributor and participant: the film’s opening dialogue commences with Cave intoning, “At the end of the 20th century, I ceased to be a human being” – a line taken from Cave’s songwriting notebooks. Subsequent lines of dialogue were developed after Forsyth and Pollard sent Cave topics by email, to which Cave would reply with his musings.

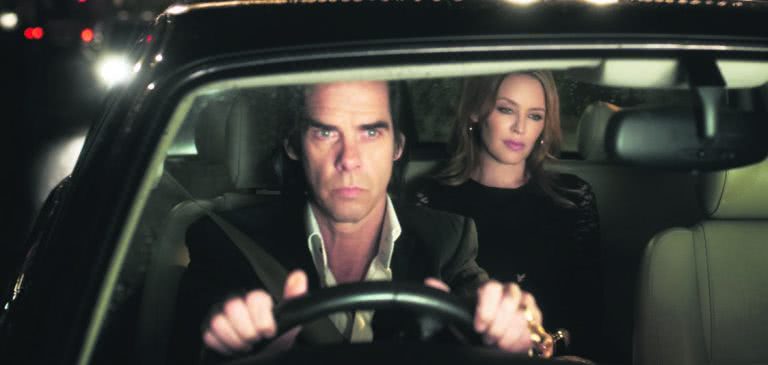

The film is punctuated by a series of conversations held in Cave’s car featuring other performers querying Cave about aspects of his art and life – there’s former Bad Seed Blixa Bargeld, actor Ray Winstone and one-time collaborator Kylie Minogue.

“The idea we had was to use the car as a sort of imaginative space, a place where we could manifest the inside of Nick’s head,” Pollard says. “The car gives us this pure and simple narrative device. It keeps the ‘journey’ of the day moving forward, but they also gave us these chances to spin off into a more creative realm. So we see these conversations like figments of Nick’s imagination.”

The brief moments with Bargeld, the brutally enigmatic German artist whom Cave worked with for 20 years, are particularly fascinating. Bargeld, who once described Cave on English television as “the greatest songwriter of the [20th] century” (Cave responded by referring to Bargeld as “immutable, godlike”), is typically frank in explaining his departure from The Bad Seeds – an explanation that apparently Cave had not previously sought, nor Bargeld had ever offered. The reason for his departure, Bargeld says in cold, clinical and Teutonic style, was that he could no longer balance being in two different bands – it had nothing to do with creative differences or personal conflict.

For the filmmakers, Bargeld’s appearance in the film “represented the idea of moving on”. “Their collaboration had been a close and special one,” Forsyth says, “and after it ended they’d never properly discussed why – Blixa just left the band. So we hoped that bringing them back together might spark a conversation around that event and some of these ideas. On set, they felt like two old friends meeting again.”

20,000 Days On Earth has as its implicit quest an investigation of Cave’s basic artistic inspiration. Cave has suggested previously that “inspiration is a word used by people who aren’t really doing anything”. It’s a sentiment that seems to be borne out in Cave’s commentary in the film: he challenges the notion of a muse in the caricatured sense of the term. Cave’s exploration of religion – which can be witnessed to varying degrees in songs such as ‘The Mercy Seat’, ‘The Witness Song’ and ‘Into My Arms’ – is explained pithily as a counterweight to his drug use.

Forsyth and Pollard acknowledge Cave’s relationship with religion “as always [being] a complex one”. In that context, Cave’s cursory dismissal of religion as a source of creative interest wasn’t a surprise to Forsyth.

“After a recent screening in New York someone asked if the film once and for all answers the question of whether he believes in God. His answer was that this is how he felt on that day. That pretty much seems to sum up Nick’s feelings on religion.”

By the end of the film it’s not clear whether the viewer has any more understanding of who Nick Cave is or where he’s going. His kitchen table dialogue with creative partner Warren Ellis is reminiscent of two old men trading tales of sporting battles of yore; when Cave describes the scene at a Birthday Party show in the early 1980s – at which a urinating German fan provoked the violent ire of the band’s late bass player Tracy Pew – it’s with a mixture of amusement and adult reflection.

The truth – if such an abstract concept has any relevance to Cave – is that he is, like so many artists, a well of contradictions. In the latter days of his tenure in The Birthday Party, Cave attempted to explain the confrontational aspect of his stage demeanour: “You’re placed in such an extreme atmosphere, there’s so much focus on you, [that] it’s a matter of pulling out the innermost, inner personality you may have, wearing that in exchange for your day-to-day exterior.”

But to interpret Cave as pathologically intense or perennially serious is superficial at best. “Nick’s one of those artists that there are lots of preconceptions about,” Forsyth says. “He’s often thought of as someone dark and serious, but he’s actually a funny and open person. Maybe that’s something the fans have become used to in recent years, and the humour seems to have bled into his songwriting. But anyone less familiar with Nick’s work might not be expecting that.”

Forsyth and Pollard make no excuses for leaving the door open for further enquiry. “We were determined to portray the Nick we know, and we feel pretty confident that we’ve done that,” Pollard says.

“It’s an honest film, and contains a great deal of truths. That doesn’t mean that all the facts and figures are correct. Part of being a fan is a thirst to know more, and we’re sure fans will have many more questions that the film doesn’t answer.”

20,000 Days On Earth (dir. Iain Forsyth and Jane Pollard)isin cinemas Thursday August 21. It’s also screening Sunday August 31, 1pm @ The James Theatre, Dungog as part of Dungog Festival.